The relations between the ego and the unconscious - C. G. Jung

Posted

This is the second of the two essays in “Two Essays on Analytical Phychology”. I originally wanted to have only one post for both, but I had already titled the old post with the name of the first essay. I guess it’s less of a hassle to just have a separate post.

This essay is divided in two parts, “The effects of the unconscious upon consciousness” and “Individuation”. The first part seemed to me more technical both in wording and aims - Jung talks at length of the problem of transference, its causes, its consequences and how to treat it; but I’m not treating anybody nor I plan to, so this wasn’t too interesting.

This I found interesting, also in the spirit of the first essay:

Dreams contain images and thought-associations which we do not create with conscious intent. They arise spontaneously without our assistance and are representatives of a psychic activity withdrawn from our arbitrary will. Therefore the dream is, properly speaking, a highly objective, natural product of the psyche, from which we might expect indications, or at least hints, about certain basic trends in the psychic process. Now, since the psychic process, like any other life-process, is not just a causal sequence, but is also a process with a teleological orientation, we might expect dreams to give us certain indicia about the objective causality as well as about the objective tendencies, precisely because dreams are nothing less than self-representations of the psychic life-process.

My takeaway is the following: if I take a hammer a smash it against the wall (with enough strength), I produce a crack in the wall. This would be just a causal sequence: the crack in the wall is caused by the hammer swinging against the wall; if I fall ill e mi prendo la febbre, the fever is a causal sequence - the fever is caused by the illness - and a consequential (?) sequence, “a process with a teleological orientation”; with the fever the body wants to bake away the source of the illness, there is an aim.

It’s unclear in which sense the body might want something, or have an aim, for the body does not have a consciousness; I use these expressions for lack of better words. The point is that dreams and spontaneous expressions of the unconscious - which by definition does not have a consciousness - have an aim and want things exactly in the same sense as a fever does, or as shivering when you’re cold does, or blushing, or yawning. They’re means to an end, they’ve been selected by evolution, they’re possibly obsolete by now, it’s up to the conscious mind to interpret them as signal, understand them and decide whether to indulge them or counter them, having the consequence of either action in mind. In this light, it’s not all absurd to think that dreams might have a message, rather than just being brain burps, side results of digesting past experiences. This is a new point of view I learned.

Nella seconda parte si approfondisce il tema di animus e anima, which was also one of the things I was curious to read more about. While not all parts of the crowded inner world Jung theorizes are mentioned - notably the shadow is missing -, the collective unconscious is characterized in great detail.

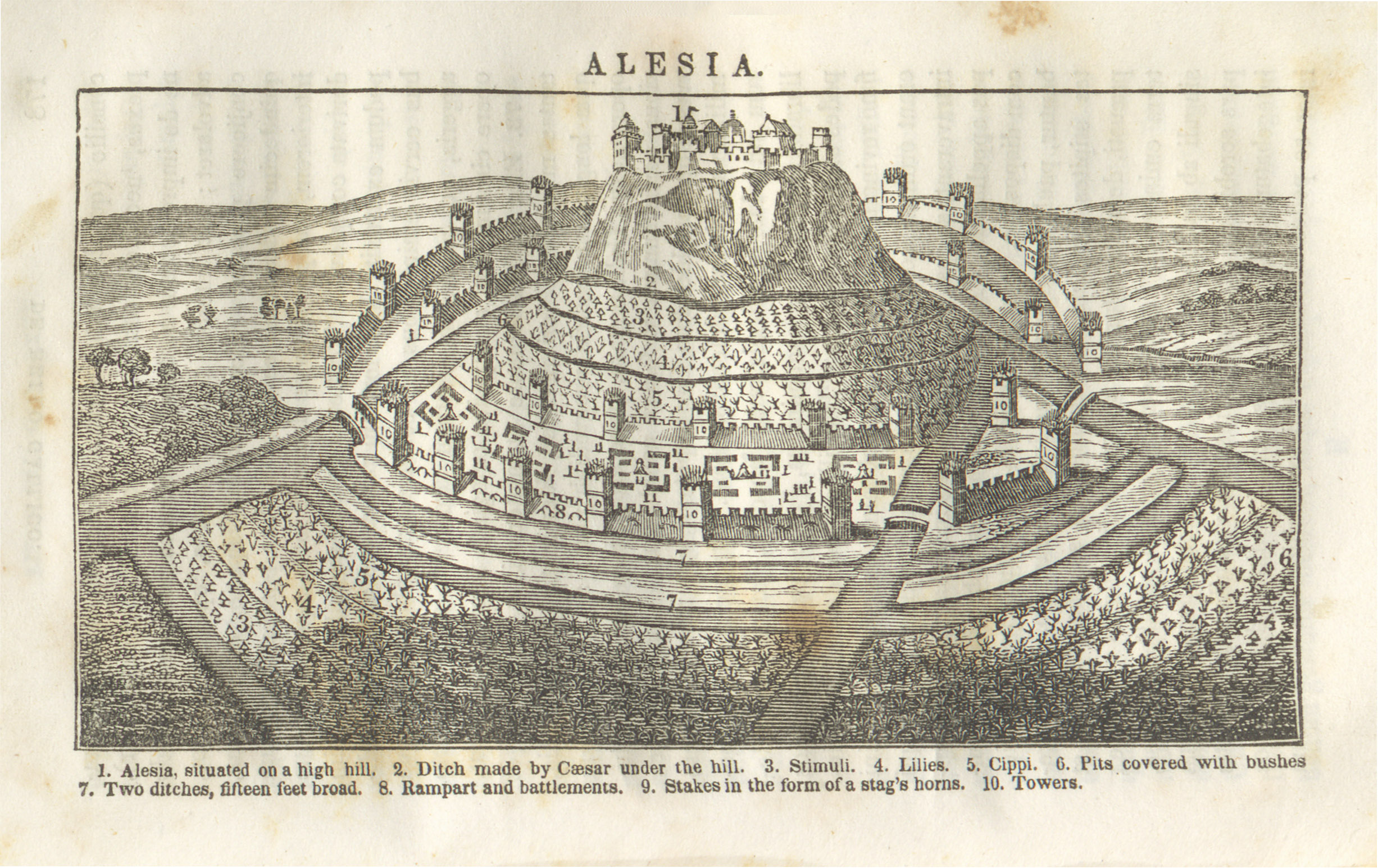

I understand it in terms of the battle of Alesia: kurz gesagt, while fighting the Gauls Caesar puts a city under siege, and while the siege is going on another angry army of Gauls comes to attack him, so that he decides to build external fortifications as well; so now there is the city of Alesia, fortifications around the city to stop the Alesians from running away, Caesar’s camp, fortifications around Caesar’s camp to stop the other Gauls from attacking Caesar, the angry army of Gauls outside Caesar’s camp. This is a map I found, from an A.J. Mason:

In Jung’s view, we are (part of) Caesar’s camp; we have an external boundary and an internal boundary, beyond both of which something else lies. Beyond the external boundary there is the external world; if we’re interested in the psychic side of it, this is mostly made up of the human society - it is the bundle of rules and norms humans are conscious of and share. We are regularly in conflict with the external world, and must come to terms with it; the face we show to this external world is what Jung calls the persona. When I go to the lawyer, I am a referring to a persona; when I marry a lawyer, I (hopefully) married the individual; the persona of the lawyer gives the individual behind it a functioning role in society. The individual shouldn’t be sucked up in the persona and should rather use it as a helpful tool to entertain relations with the external world.

All of this is now true for the internal world as well: the unconscious is not just made up of thoughts too painful or unripe to bring to consciousness - they’re also in Caesar’s camp -, but also of external stimuli which come from the unconscious equivalent of the conscious external world, which is what Jungs calls “collecive unconscious”. The spiritism of ancient tribes is according to Jung a way of projecting the collective unconscious in the external world - the collective consciousness, so to speak. Our consciousness has to deal with the collective consciousness, our inconscious with the collective unconscious, and unconscious and consciousness have to deal with one another; the persona lies at the interface between consciousness and collective consciousness, the animus/anima at the interface between inconscious and collective unconscious.

An ill-determined persona is the hallmark of the socially unfit individual, who is either unhappy because he’s fully identified with its two-dimensional role in society or because he is suo malgrado an outcast; an ill-determined animus/anima is just as dangerous. Ignoring the need of animus/anima, their needs and the existence of the collective unconscious is just as reasonable as ignorings the need of a persona, its needs and the existence of the external world. The bottom line being: please don’t do that.

The two sides of the collective commented by Jung:

The two opposing “realities”, the world of the conscious and the world of the unconscious, do not quarrel for supremacy, but each makes the other relative. That the reality of the unconscious is very relative indeed will presumably arouse no violent contradiction; but that the reality of the conscious world could be doubted will be accepted with less alacrity. And yet both “realities” are psychic experience, psychic semblances painted on an inscrutably dark back-cloth. To the critical intelligence, nothing is left of absolute reality.

This quote reminded my of this poem from Pessoa, a true expert of personae:

The construction of a collectively suitable persona means a formidable concession to the external world, a genuine self-sacrifice which drives the ego straight into identification with the persona, so that people really do exist who believe they are what they pretend to be.